The Underwater Wood

From Jim's NotesSlab wood which is usually used for firewood is the wood that is first cut off the log. These pieces include the curved outside of the tree. I was able to get some of this wood when the logs were were being pulled from the Bay by commercial enterprises.

Being slab wood, I cut to cut them very carefully to get the incredible grain that it had to offer. In white oak, this meant cutting in a quarter-sawn manner to show off the figure. Quarter sawing is in essence cutting the tree in wedges with each cut going towards the center of the tree. This results in narrow strips but with fabulous grain. The story of the logging on Georgian Bay is written on the bottoms of the chargers - each charger having part of the story. Some of the wood in these chargers is over a thousand years old. I have made a set of four chargers for this show. Two are elm, one is white oak and the fourth one is beech. In the naming of these pieces, I lament the fact that we never seem to learn. In our greed we destroy and when we destroy we can never have it back the way it was. Then it was the indiscriminate clear-cut logging of thousands of square miles of Ontario. Today it is gravel, minerals and oil. Like our ancestors we are throwing away what we have to acquire something we think we need. My chargers are: "Resurfacing", "Bearing Witness", "What Once Was" and "Now Only a Story". |

The Story

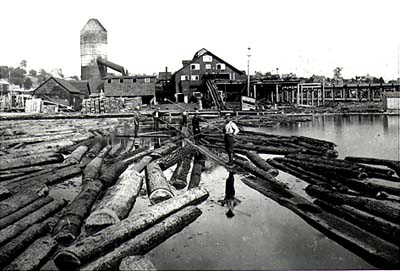

Logging took place on the shores of Georgian Bay for over 200 years. Starting in the 1700's and continuing until early in the twentieth century, the sawmills along the Bay were busy. First they took the pine. Pine trees 50 metres tall were common. Old growth pine was a highly prized wood since huge, knot-free boards were the rule rather than the exception. Pine was common and easy to cut, thus used for paneling, floors and furniture. Tall white pines with high quality wood were known as mast pines. A 100’ mast was about 3’x3’ at the butt and 2’x2’ at the top, while a 120’ mast was a giant 4’x4’ at the bottom and 30” at the top. J. R. Booth was probably the greatest of the "lumber barons". At one point he had secured timber rights to 7,000 square miles in Central and Northern Ontario. In the early 1880's Booth and his competitors were producing 500 million board feet of pine per year. (This is the equivalent of filling an entire professional league baseball stadium with solid pine to a depth of 230 feet.) The Georgian Bay Lumber Company was turning out 300,000 board feet of pine per shift! In 1892, one of Booth's mills produced 140 million board feet of lumber, more than any other mill in the world. After the pine was pretty well depleted the loggers came back for the hardwoods. Birch, white oak, maple, beech and birdseye were cut and sent to the mills. They didn't select certain trees, they took everything. The method was called "clear cutting". Many of the trees taken were "first growth". The grain was so tight that it was almost impossible to count the year rings. The figure in the beech, white oak, maple and birch was stunning. It is rare to impossible to find similar woods in our forests today. Hardwoods such as oak, birch, maple and beech in excess of a thousand years old were also common. The hardwood logs proved to be a lot more trouble than the pine. Being considerably denser than the softwoods, they rode very low in the water and by the time a log boom had been towed the length of Georgian Bay as many as 50% had sunk to the bottom. A number of methods were tried to alleviate this problem but most were expensive and ended in failure. A time-consuming procedure that proved effective was chaining the heavy hardwood logs to buoyant cedar or dry pine logs. When lumber prices were good it was worth the trouble. These logs were floated down the length of Georgian Bay to the sawmills. Logs cut during the winter were left on river banks to be driven down stream to Georgian Bay in the spring. These logs were formed into booms as large as 25 acres in size and containing as much as eight million board feet of lumber. The best speed these booms could make was about one mile per hour, taking as long as ten days to reach the sawmill. In the 1930's people were becoming aware of the environmental damage that had been done by the unrestricted logging over the last 200 years. Habitats were destroyed, drainage was altered and the seeds of climate change had been sown. Municipalities started to protect lands by restricting the issuance of timber rights especially in "cottage country". The last of the lumber barons circumvented the spirit of the new laws by purchasing the land and islands for their cottages and summer homes. Once they owned the land, they also had the timber rights and they clear cut the last of the prime stands. Only after the last of the original timber had been cut did the sawmills fade away. Just as the last of the prime timber was being cut, others started to realize size of the treasure that was lying on the bottom of Georgian Bay. People started to bring logs to the surface by dragging a set of tongs across the bottom until they snagged a log. After the second world war, scuba diving and side-sonar took the guess work out of the recovery process. As the emerging salvaging businesses became profitable, governments took an interest and started regulating the activity. There were issues surrounding the ownership of lost logs and the disturbance of lake bottom sediments and fish habitats. "Finders keepers" now came with a royalty on any timber salvaged. |